A bomb blast in Auckland’s down-town harbour zone would wipe out a sizable chunk of the city’s plumbing, brickies, and electricians. An army of sweaty tradesman is urgently beavering away on new apartment developments hugging the water’s edge.

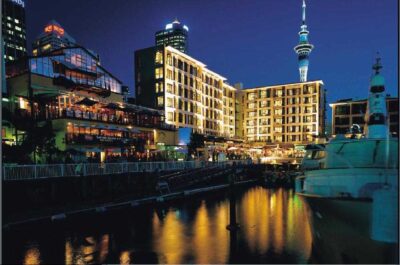

Most projects have a firm “no-excuses” deadline: the start of the America’s Cup showdown in February. The glittering “big boys” boat race has accelerated the timetable for a makeover of the once scruffy precinct.

Hard on the heels of the luxury highrises have come designer bars, restaurants, cafes, and foreshore walkways. And unlike the past where hyped events the hospitality trade to the wharves only to see crowds disappear soon after, the new crop of developers say the facilities are here to stay. The difference is more people are living in the city. Apartments are springing up in the shadow of retail, entertainment and education centres. “The apartment market in Auckland is established and will continue to grow,” says Nigel McKenna, director of Melview Developments.

Two luxury waterfront developments in the city’s Viaduct Basin – The Quay and Watermark – are among Melview’s extensive residential construction portfolio. The company builds more than 200 houses, terraces and apartments a year. McKenna’s faith in the growth of medium and high-density housing is based on the experience of overseas cities.

Auckland inner city apartments, he says, account for only 1% of the residential market. “All major cities have significant inner city populations. The apartment market here can easily triple.” Pressure on land suitable for housing, people growing tired of commuting, and lack of convenient public transport from the CBD to outer suburbs, all contribute to the appeal. While terrace housing on the fringes of the city is growing faster than apartments – New Zealanders still relate well to a back-door and courtyard, says McKenna – he believes the over 50s will spur the highrise market.

“Older people want security and an elevator.” While serviced apartments, usually linked or run as a hotel and attractive to investors are a large chunk of new developments, the market has quickly adapted to the demands of the latest wave of owner-occupiers. “Buyers are more savvy,” says McKenna. “They can sort quality from rubbish. Most early conversions – old offices and commercial buildings – were shockingly bad. Bedrooms had no windows and there was no noise insulation. They can’t hold their value.”

Almost a decade later, buyers spending upwards of $300,000 have a strict shopping list of requirements. Views, sun, security and parking are musts. So are double glazing and sound-proof walls. Air conditioning will be assumed, along with high ceilings, small but modern kitchens – city apartment dwellers eat out a lot, says McKenna – and a quality bathroom with bath, separate shower and twin wash basins. And even buyers of modern one-bedroom apartments ($90,000-$130,000) expect a gym, spa and sauna.

The surge of inner city residential development is finally creating a heart for Auckland, says McKenna. “While Newmarket is long established as the retail district, Parnell the boutique shopping destination, and Ponsonby the restaurant mile, Queen St has looked shabby and deserted.” The splurge of waterfront apartment construction is rejuvenating the bottom end of New Zealand’s busiest city, attracting smart new retail stores, cafes and entertainment venues. Existing stores are being spruced up and designer outlets are replacing T-shirt and trinket outlets.

The downtown remodeling is being matched by impressive developments at the other end of Auckland’s main drag. The opening of the giant Force Entertainment Centre, says McKenna, is breathing new life into the top end of the street, which includes the Aotea Square conference precinct and refurbished town hall. “Aucklanders will be able to take pride in their city centre when this major redevelopment is completed.”